Anatomy of a Swift Fall

Womanhood on trial

The Sunday Letter #37

If your TikTok algorithm is as relentless with Taylor Swift content as mine is, you’re well aware that Swift is currently on a two-year world tour/career retrospective known as the Eras Tour. Since starting the tour in April of this year, she has re-released two albums and a concert film. She’s also become a billionaire, the first musician to do so “solely through music alone,” per Forbes, though of course such a phrase obfuscates many realities about the capitalistic shrewdness required to “earn” a billion dollars. All in all, she has attained global domination at only 33 years of age, and she did it with glitter pens, multicolor nails, beautiful gowns, and a dream.

Last night, Swift played her second show in Argentina after a months-long break in which she began publicly dating football star Travis Kelce. I’ve never seen Swift live, and I don’t currently have plans to, after failing to get on the waitlist here in Canada. But the thing about Swift, as I ranted to my husband last night, is that even when you’re missing out, the rabid Swiftie culture is such that you don’t even have to be there to experience it.

After returning home from dinner with my in-laws, I laid in bed catching up on the concert along with millions of other fans around the world. The concert wasn’t even over yet, and I was already rewatching her belt “Out of the Woods” in the “surprise song” section, in which she performs a song that she won’t play any other time on the tour.

L asked what I was watching, and before I started to explain my deep fascination with Swift, I prefaced it the way I always do: “It’s funny, I’m not necessarily “a fan” but I have to admit she’s a marketing genius…” But as I started to dissect what makes her such a powerful icon to so many, I wondered why I’d chosen to preface it the way I had.

Swift’s music offers a soaring, emotional resonance for fans, with lyrics that are both ambiguously universal and highly-specific. But her real power is derived from the fact that to love Swift is to be borne into a built-in friend group. Like Avril Lavigne was for me, Swift is an emotional conduit for fans at any stage of life. Videos of young women belting their hearts out to Swift’s songs about heartbreak may seem silly to some, or extremely resonant to others, who remember being young and feeling like our feelings were too big for our little bodies.

Her fans know everything about her; they’ve watched every video, combed over every lyric, analyzed every social media post looking for clues. It’s much been joked that Swift has single-handedly diverted an entire generation from QAnon-style conspiracies by forcing them to focus all attention on solving her puzzles with military precision. But not just that: her rise to stratospheric fame over the past few years had coincided beautifully with TikTok’s rise over the pandemic, with teens searching in droves for community online. Her fans can communicate globally in real-time, observing her at all times from every lens. They are, for all intents and purposes, in love with her, whether they realize it or not. Her pain is their pain; her love is their love, and this hasn’t been more evident than in her new relationship with Kelce.

There are countless videos at this point, from every angle, of Swift running into Kelce’s arms at the end of last night’s concert, giving him an on-camera kiss for the first time. Her fans are losing their minds over this moment online, though I find it most interesting for what happens a minute earlier: when Kelce walks inside, only to be summoned back outside so that the cameras can catch Swift running into his arms.

Already, countless videos have sprung up betting on how soon these two will be engaged, married, and procreating. While Kelce is the third man she’s been linked to romantically this year (good for her!), I very rarely see her painted as an independent, artistically-fuelled creative at the top of her game; rather, the public sentiment often tends towards the assumption that now that she’s dating a fan-approved man, it must automatically equal wedding bells. Others predict that she must be aching to have babies and quit touring. And maybe that’s true, but absent any statement of proof on her feelings in either direction, I’d find that pretty patronizing if I were her, tbh!

I remember watching The Golden Globes ten years ago when Tina Fey and Amy Poehler made a joke about Swift dating around. Swift was 23 at the time, I was 18. The public sentiment towards Swift’s discomfort was pretty typical of the time: She’s a bitch if she can’t take a joke. I believed this, and probably internalized it too. It was only when Swift returned to this era with the re-release of Red that the world seemed to reckon with its past treatment of her. Not only was there a sentimental element to revisiting extended songs such as the Jake Gyllenhaal-inspired All Too Well, but it offered Swift vindication too. Performing on SNL, Red was a victory lap ten years on, with Swift the phoenix rising from the ashes.

Though this “vindication,” is also up for debate. Some argue that Swift perpetually victimizes herself, recalling the Kanye/Kim drama of yesteryear and suggesting that she may have deserved PR crises such as “Snakegate.” In fact, this essay was inspired, in part, by a TikTok creator named NotWildlin, who recently argued that Swift is forever positioning herself through a metric of girlhood, unlike Beyonce, whose music is more explicitly “grown up.”

As I explained to L, Swift has a decidedly millennial earnestness that would be considered cringy to her Gen Z and Gen Alpha acolytes, were she anyone else. There’s even an entire Instagram account dedicated to encouraging her to be more stylish. Yet she’s reached a level of power that is veering on untouchable, through sheer force and brilliant manipulation of parasocial machinations. Her cultural omnipresence is unparalleled. She received six Grammy nominations last week, and she’s behind only Elton John in the race for the highest-grossing tour of all-time. It’s undeniable that she is everywhere, that every fan feels like they have a personal connection to her, a connection they’d be willing to go to war for.

But what happens when a woman becomes a god? And what happens when that god becomes omnipresent? Is it possible for a woman to reach the status of unimpeachable?

*

I saw Anatomy of a Fall (dir. Justine Treit, 2023) a few days ago, and I’ve been haunted by it since. The film follows the murder trial of a woman accused of killing her husband, and it examines the realities of truth as both performance and artifice. We don’t see the husband’s death onscreen, only the ripple effects outwards, as all eyes turn to his wife. Was he jealous of his wife’s creative success, her sexual promiscuity, her ruthless ambition? Did this amplify a lack in him? Did this lead to his murder, or his suicide? It’s an explanation that (spoiler alert) Triet doesn’t offer us. Instead, the film is entirely left to the audience’s interpretation, a Rorschach test for one’s perception of an ostensibly truthful woman’s credibility.

The film was subversive in its treatment of the marriage at its center: through flashbacks, we see Samuel, the husband, butting up against his wife’s success as a writer, while he feels he has held himself back to care for their son and manage their household. She counters that they live in his hometown, away from her German motherland. It’s a brutal fight that comes near the film’s end in which both characters contend with their disappointments in themselves and in each other.

Triet, who directed the film from a screenplay she wrote with her husband Arthur Harari, acknowledged in a recent New Yorker interview that she also does less childcare than her husband. Sandra is “a female character who’s a creator, who writes books, who is in the position, at last, of taking time to write, means that it’s the man who suffers.” In other words, a ‘bad’ wife.

And while the film is an exercise in audience empathy, it turns slightly as we see this ugly side of Sandra, the one that might be capable of pushing her husband out of a window. For her own freedom, she must prove that her husband was miserable in their life together, but she can’t make herself believe it. She can’t extract his misery from her own: it’s two sides of the same coin, she pleads to the prosecutor.

I was struck by the dizzying claustrophobia of the film, in which womanhood itself seems to be on trial. In a W Magazine interview, star Sandra Hüller refers to her character as a “perfect example of a grown woman who knows what she does, who knows about the things people think about her, about the projections on her, but at the same time about her own reasons to do things and to be totally fine with the consequences of her actions.” In fact, on whether her character was “guilty” or not, for all the complications of such a term, Hüller revealed: “I never really decided anyway…I wanted her to be a person that could do it. I wanted her to be a dangerous woman. We don't see that very often and why not?”

*

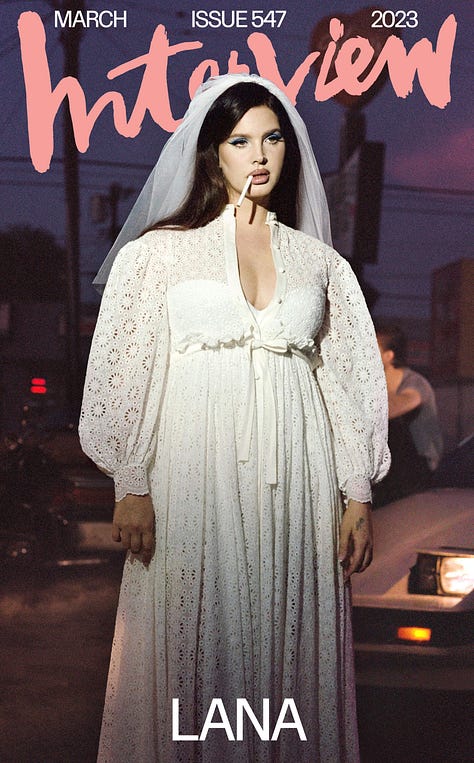

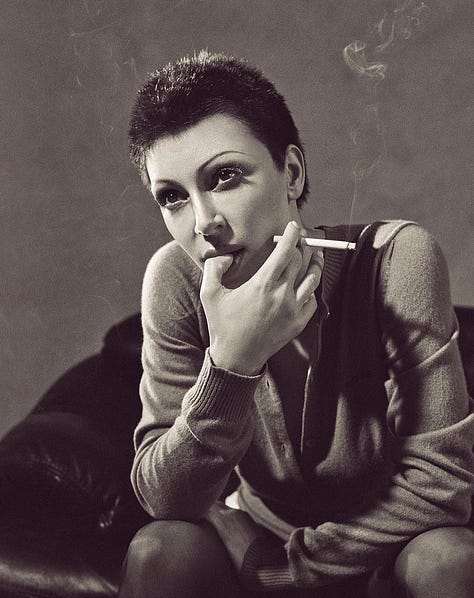

The other day I came across a video about Nadia Lee Cohen, and realized that multiple iconic photographs I’d admired in the past had been her work. How had I never connected the dots? Cohen’s work represents a perfect through-line from Swift to Hüller, in that representations of womanhood are presented through hyper-augmented artifice or superficial realities. If Swift is the über-woman, the quintessential pop star who’s finally found her match, then Hüller represents the cost of a woman’s ambition in turn. A woman can have one image of who she is, but once it’s distorted through the funhouse mirror of social media, or the funhouse mirror of the criminal justice system, or on-and-on-and-on, who does she become? As Triet noted in her New Yorker interview,

“It’s not a question of truth; it’s a question of convincing.”

This week’s recommendations

In preparation for seeing Priscilla this evening, I watched Sofia Coppola’s 2006 film Marie Antoinette. In signature Coppola style, Marie was both aesthetically beautiful and morally vacuous. While some critics have lambasted Coppola’s treatment of Antoinette as overly-flattering, others have suggested that this critique is itself indicative of Coppola’s greater argument: that womanhood can be a gilded cage, an existence more constrained and painful than the reality of a murderous death. Coppola’s use of an anachronistic soundtrack and props lend themselves to this argument; when not entirely loyal to the subject matter, she is a master of bending visual storytelling to her own narrative whims, where the substance is often found in what is lacking. I’ll share my thoughts on Priscilla next week, but if you've already seen it, what did you think?

Hailey Colborn on growing up online and loving her computer:

“I had twelve Webkinz. I don’t remember my login. Are they dead? Does my computer mourn them? Did it have its own clunky coming of age? Slimming with each year and acquiring more and more storage in tandem with my own collecting of memories, growing and shrinking in monitor and battery and gigabyte as I starved and stuffed myself, trying to control the pictures I’d let it hold onto and share with its brethren to show to mine.”

Esquire on why it’s never been harder to make it as a writer: “If you're going to make it as a writer today, you have to be compelled to write regardless of how much money it's going to earn you…because it's probably not going to earn you enough to only do that.”

From Majuscule, why bimbos and tradwives are cut from the same reactionary cloth: “If some of us choose to be dehumanized by men, how do we ensure that they don’t then feel more empowered than they already do to dehumanize all women?”

Moira Donegal on the end of Jezebel, “one of the last remaining feminist institutions.”

Alexa Chung on turning 40: “Your friends will be one of the great romances of your life.”

I love any and all analysis of Taylor Swift. She was my girlhood but as I’ve gotten older I’ve become more disillusioned by her and her opulence. But also I feel for her more and more each year. She’s been in this intense spotlight since she was 15, she’s had every relationship she’s ever had analyzed and viewed by all. Like you can’t help but feel for her to some extent.