A Reminiscence on Youth and Our Former Selves

Karla Méndez on depictions of girlhood and missing youth

Welcome back to Solitary Daughter, an arts and culture newsletter. This week: the wonderful Karla Méndez writes a guest letter on photographic depictions of girlhood and the pulsing nostalgia for youth. Thanks for tuning in, and stay tuned for a new link round-up later this week.

When we’re young, we can’t wait to grow up. We dream about where we’ll be when we’re adults. Whether it’s what we’ll study in university or what career we’ll have, when we’ll get married or to whom, or parenthood, the future when we’re children feels as if it’s overflowing with endless possibilities. “The world is your oyster,” as they say. But the future comes at us fast.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve had this fascination with nostalgia and reminiscence, particularly about my teen years. Though I am tremendously appreciative of the life I have and what I have accomplished thus far, I find myself filling up journal pages looking back on and memorializing a time in my life that felt like I was on the cusp of an immense freedom. A time that felt like the world was getting ready to open up for me. And while I could say that the general lack of responsibilities and promise of freedom are the primary reasons why I continue to reminisce, that would be too easy and would enable a surface understanding of this compulsion.

There’s a feeling of refuge in looking back that I find alluring, particularly as my life has gone through transitions over the last few years, these moments have occurred often. I think this is one of the chief reasons why I am bewitched by girlhood and the transition to womanhood. Girlhood felt like waiting with bated breath, counting down to when I would be able to finally breathe, while adulthood has at times felt an inability to take a deep breath. And it makes me think, what was I in such a rush for and why do I now look back on girlhood with so fondness and a desire to reclaim those moments and that girl I once was?

I grew up watching and reading The Virgin Suicides, which I would say is what a lot of people instinctively think of when they think of girlhood. The Lisbon sisters are a personification of youth, teenage girls who are on the precipice of adulthood and as such, are trying to discover who they are as individuals. Yet every attempt is met with resistance by their domineering mother. While I would consider this my introduction into the depiction of girlhood, and which still remains a favorite, in recent years I have discovered and gravitated to similar representations in photography. Photographers like Francesca Woodman, Justine Kurland, Helen Salomão, and Sally Mann skillfully and faithfully capture the varied emotional and physical experience of girlhood and youth.

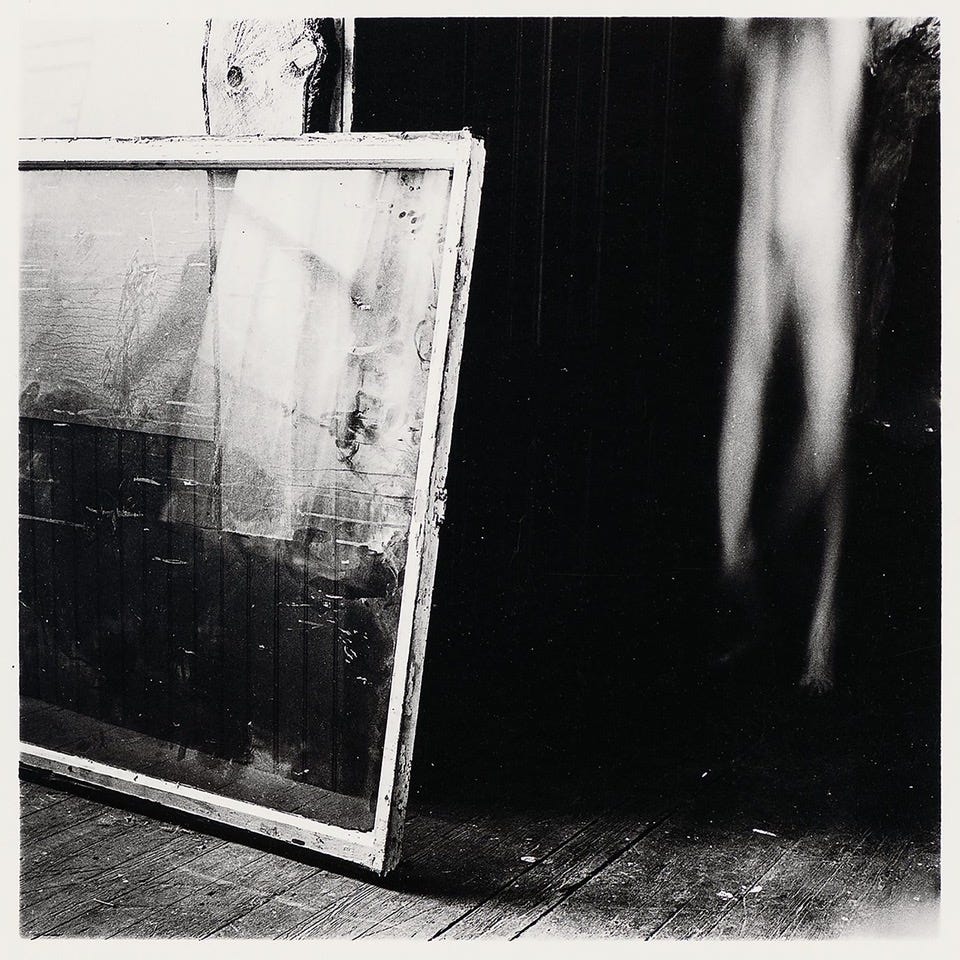

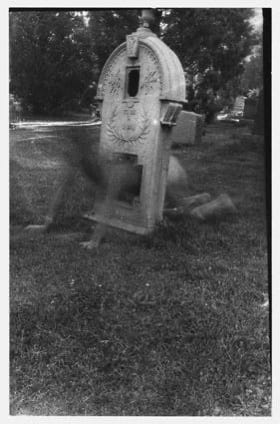

Images by Francesca Woodman in particular have served as a guiding post in this continuous investigation of girlhood and self. The photographer, who passed away at the age of 22, amassed in her short life 10,000 negatives and 800 prints documenting herself from the age of 14 to 21. Woodman often took these photos in locations that were abandoned and decaying. I couldn’t help but to think of the parallels between the rooms and sites she chose, and this idea of girlhood being a period in which we at times feel abandoned and which feels like who we once knew ourselves to be is crumbling around us.

When I first came across the work of Woodman, I instantly made a connection between her work and The Virgin Suicides. There was a familiar feeling of loneliness present in both that spoke to how the experience of girlhood often makes us feel as if we’re an island – alone and unreachable. Images like Untitled, Rome, Italy (1977-1978) and Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island (1975-1978) in particular through their haze capture both the speed at which girlhood passes, yet forever feels like we’re caught in its current.

In most of her photos, Woodman is not only the photographer, but the model, and just as my journals are an archive of the thoughts, experiences, and interactions that constructed my girlhood, I found her work to be similar in its attempt to document her existence. I find that sometimes when speaking of or actively going through girlhood, it feels like we’re losing parts of ourselves, discarding pieces in random places, sometimes with the hope of revisiting our former selves. Through her work, the photographer has left behind fragments of herself, a trail that she could have followed to find her way back.

Woodman’s work has been described as haunting, which I would say is an apt description, but perhaps for different reasons. Photos like Untitled, New York (1979) and Untitled, Boulder, Colorado (1972-1975) feel haunted, if only because they feature traces of the photographer. A figure can be made out, but only abstractly, foregrounding the idea that who we once were, that is the parts of ourselves we are shedding as we progress through girlhood are forever walking with us, haunting us. We are unable to rid ourselves of them because they continue to be a part of us, a reminder of who we were, but also of who we can be.

This idea of haunting and leaving behind traces of existence reminds me of artist Sophie Calle’s 1981 series of images she took while working as a chambermaid at the Hotel C in Venice. In having access to the rooms of guests, she was able to capture various items left as they were throughout their rooms. Though they were fairly common objects like shoes, suitcases, clothing, and medication, each one was linked to the person to whom it belonged, housing a story. And while seemingly unrelated to the concept of girlhood, there’s an element of voyeurism that is familiar. Through her images, Calle, like Woodman, opened a door unto moments and scenes that typically aren’t shared. What is seen when we think no one is looking?

I remember having a visceral reaction to Woodman’s photos the first time I saw them. They felt familiar, as if I was looking at myself. There was a level of discomfort, perhaps because I saw in them my repeated attempts to reconnect with myself. I identified the arduous task we undertake during girlhood of trying to find ourselves. To evolve into a version of ourselves that is deemed fit to participate in adulthood. Maybe I find myself drawn to Woodman’s work because it balances between girlhood and womanhood. Or it could be that like her, I am still tightly holding on to girlhood through my musings. The messiness, the uncertainty, the expansiveness of it. Or maybe, Woodman and I, through our ruminations, are actively grieving the person we once were.

Karla Méndez is an arts and culture writer obsessed with analyzing art through a historical lens. She has written for the Boston Art Review, Black Women Radicals’ Voices in Movement, Elephant Magazine, Teen Vogue, Polyester Zine, and elsewhere.

I felt incredibly seen reading this. Glorious writing!

beautiful piece