I Want the Thing Itself

On not forgetting

The Sunday Letter #1

It’s cold in the prairies. There’s less snow now, and the days feel longer, but it’s still bone-chillingly cold, and I haven’t been leaving the house. I sense, though, that the cold fog is lifting. My annual late-winter identity crisis is starting to pass, and I’ve felt the same push towards writing that I felt at this same time last year (when I first started this newsletter). It’s a push that tells me to sit with my thoughts, write about them, soak in them, rather than shoo them away.

I’m resolving, here and now, to aim for weekly posts—a mix of writing as well as observations about the media I consume. I’ve been keeping weekly notes about what I’ve been watching and reading to help guide my thoughts, but as an obsessive list-maker this has been an interesting practice. In the past, repetitive list-making has been a symptom of my OCD, something that comes out only when I am most stressed. But apps have glommed on to/perpetuated a cultural obsession with Not Forgetting: how many apps on your phone do you have for tracking every minute of your list? Without looking, I can think of at least a few that are on mine: period trackers, book trackers, movie trackers, habit trackers. All consumption must be catalogued, not forgotten—why? Probably to keep us on these apps, to log our interests for the algorithm, to influence each other. For me, this translates into utter fear about losing all the photos I have digitally stored. And to be honest, if I think for too long about digital storage and how naively complacent we all are about the safety of online storage systems, I start to spin out!

Nonetheless, this list-lover persists, but hopefully in a more ~mindful~ way, that is, by appreciating the work I consume for how I can implement its teachings about craft, art, and/or life into my own life. Without further ado, a list of what I consumed this week, from a woman fearful of lists:

This week’s recommendations

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed (2022, dir. Laura Poitras) “I’ve often used photography as a sublimation for sex. It’s often better than sex,” Nan Goldin muses in Laura Poitras’ Oscar-nominated documentary, which begins with a retrospective of Goldin’s decades-spanning collection of photographs such as The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. Early on, one gets the sense that Goldin is obsessed with memory-keeping. She’s angry, too. Angry at the early death of her sister whose wild spirit was repressed by her parents, angry at the AIDS crisis which stole so many of her loved ones (Goldin’s close friends David Wojnarowicz and Cookie Mueller make appearances), and angry at the profiteers of the opioid crisis after she herself nearly succumbed to a dependency on painkillers. The through line, for Goldin, is art. All the Beauty is part-tribute to Goldin, and part-takedown, as Goldin leverages her considerable art-world influence to implore the world’s most famous museums to divest from the Sackler family, owners of Purdue Pharma, who enriched themselves through the opioid crisis that nearly ended Goldin’s life. While at times uneven, the documentary is an informative look at how billionaires launder their reputations through the art and literary world (only to receive puff pieces in The New York Times, à la Elizabeth Koch, which, between this article and all the anti-trans coverage they’ve been issuing, is really earning my un-subscription). “The wrong things are kept secret,” Goldin notes, “and that destroys people.”

Pulp Fiction (1994, dir. Quentin Tarantino) “Don’t you hate that?” “What?” “Uncomfortable silences.” While long and meandering, at times aimless, I enjoyed watching Tarantino’s early work (I’m saying this as Not A Fan of Once Upon a Time…) Sally Menke’s editing and Uma Thurman’s brief turn onscreen are stand-outs.

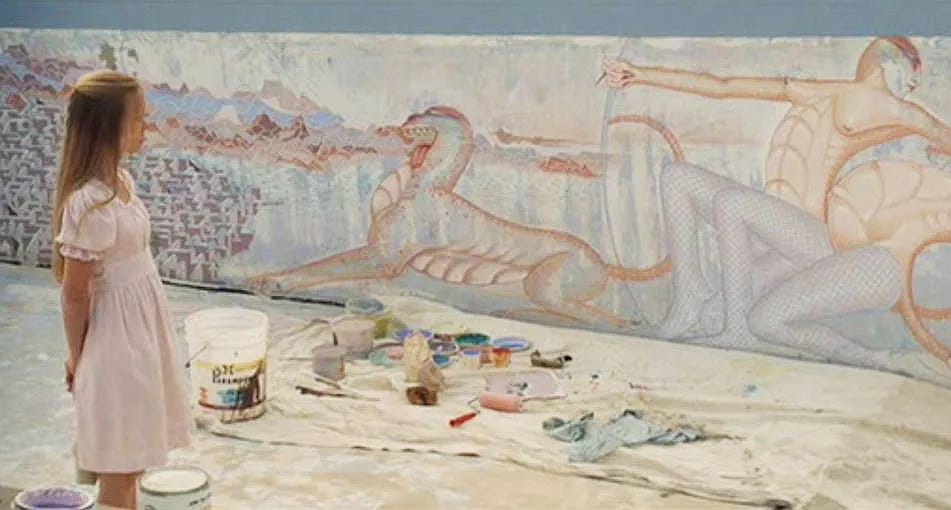

3 Women (1977, dir. Robert Altman) “You’re the most perfect person I ever met,” says Pinky (Sissy Spacek). “Thanks,” says Millie (Shelley Duvall). This elusive, genre-shifting cult classic set in the California desert in the 1970s is dreamy, if not a bit slow. Though things pick up halfway through as we notice that the porous nature of both women’s identities leave them susceptible to shape-shifting. A worthy watch if not just for the incredible set design. “I’d rather face a thousand crazy savages than one woman who’s learned how to shoot,” the exploitative landlord tells Millie, unaware that in this film, women seem to hold most of the power.

Doctor Strange Love: Cookie Mueller’s surreal advice for living by Natasha Stagg in Bookforum. “Still, something’s better than nothing.”

A Lost Interview with Clarice Lispector in The New Yorker. “I was born in Ukraine, but already fleeing.” Having recently read Água Viva from Lispector (perfect, brilliant, I’ve never been the same), I was delighted to find that she is as candid and clever in interviews as in writing. When the interviewer asks whether she prepared her first novel with a novelistic structure in mind, she responds, “Look…can someone give me a cigarette?” Later, she is asked whether Near to the Wild Heart is named after a James Joyce line: “It is. But I’ve never read anything by him.” God, this is a Novelist! Is there an author that’s influenced you most? “As far as I know, no.” !!!

I’ll leave the rest for your enjoyment but would be remiss not to include one last fantastic line: “I don’t write as a catharsis, to get something off my chest. I never got anything off my chest in a book. That’s what friends are for. I want the thing itself.”

Do Female Artists Have to Choose Between Motherhood and a Career? in Elephant. What happens when the urgency of motherhood intersects with art? “I gave up any hope of having a career as an artist but lived with the identification of it,” one artist shares. In this shattering interview, twelve women discuss their experiences of being artists and mothers: “Being a mother comes first, but I was always an artist.” Another laments the way her son treats her art as a hobby: “Where in his education has he seen any images or TV programmes of mothers who are artists and appreciated for being so?”

*

New word of the week: ekphrasis (ek·phra·sis) — a literary description of a work of art.