The New Luddites

The future is an invasive force

Last week, Universal Music Group–home of Taylor Swift, BTS, Drake, Ariana Grande, and more–removed all of its music from TikTok due to a licensing dispute. Coincidentally, TikTok has also begun offering creators increased viewership if they post horizontal content, in a move many argue is meant to make the platform more competitive with YouTube. As social media whisperer Jules Terpak tweeted, the loss of the UMG catalog could be detrimental to TikTok’s competitive edge in the video platforming space, and moving towards horizontal uploads is just plain baffling in light of the trajectory of digital media up until now.

So, let’s go down the rabbit hole of how digital media became inextricable from the aspect-ratios through which we consume it today.

Per A24, the classic 4:3 aspect ratio referred to the size of the film stock, four-by-three inches. But the introduction of sound into movies meant that “the size of the image needed to change slightly to account for the additional information.” Dubbed “The Academy Ratio,” the new size was a bit wider but “essentially” the same as 4:3. It also required that actors stand unnaturally close together in order to fit in the frame (a frustrating dynamic for modern audiences used to a bit more distance).

But then televisions started arriving in every home, offering the same viewing experience without the inconvenience of leaving the house. In response, widescreens got even wider in the 50’s in order to “provide a cinematic experience that was going to be different from a TV experience.” And the ratios have only widened, going from 4:3 to IMAX to The Sphere in under a century. We literally cannot stop finding new ways to watch the same old things.

For many years, TikTok has been one of the main sources of media consumption for teens. In response, content has been reshaped to fit TikTok’s borders, rather than the other way around. Case in point, this Saturday Night Live short from last week’s Dakota Johnson episode. Typically, videos uploaded to TikTok will crop out anything that doesn’t fit within the 9:16 border, with the video automatically centered on the screen. But I’ve noticed that SNL’s TikTok account, rather smartly, seems to individually re-center every shot rather than allowing TikTok to just center the frame naturally. Here’s the same shot of the Please Don’t Destroy boys on two different platforms:

The version on the right is much more likely to grab the attention of a TikTok user scrolling vertically through their For You Page on a Saturday night, since it would fill the screen without leaving those awkward black bars above and below. It’s also reminiscent of Please Don’t Destroy’s earlier videos that landed them on SNL in the first place (if you don’t count already having famous SNL-adjacent parents). And whereas younger generations have always eye-rolled SNL for being ‘out-of-touch,’ I can’t help but feel that having extremely-online younger writers on staff has helped usher in a new generation of young fans. They’re joking about the Stanley cups lead story and Josh wine, plus they’re booking Gen Z icons like Ayo Edebiri, Timothee Chalamet, Jacob Elordi, and Renee Rapp to appear.

But most importantly, they’re letting this generation’s Lonely Island reinvent their social media game, much like Andy Samberg and co. had to do when they ushered Lorne Michaels into the YouTube era. And it seems this same digital reincarnation is already underway: I don’t have cable, but I can tune into the SNL TikTok account on a Saturday night to see that week’s monologue live-streamed, as thousands of other viewers comment on the action in real time, all of us watching a horizontal show through our vertical screens.

*

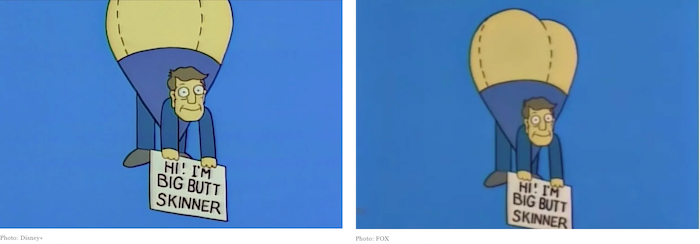

In 2019, when Disney+ began streaming The Simpsons, the classic 4:3 ratio was scrapped in favour of a cropped 16:9 ratio, which resulted in the loss of a significant portion of the show’s visual gags: “cutting out 25 percent of the screen means cutting out jokes, ruining visual gags, background details, and Easter eggs placed there by the writers and animators… Simply put: The 16:9 format is not the show as it was intended to be viewed.”

But the inverse, of aspect ratio causing viewers to see too much, is also possible. In 2015, eagle-eyed Netflix users began reporting errors in episodes of Friends specifically due to Netflix changing the show’s original aspect ratio from 4:3 to 16:9 for widescreen. Viewers familiar with the original suddenly got a bizarro-world version, one with microphones and stand-ins creeping into view, things never meant to be exposed suddenly on full display.

And it’s not just the fact that streaming services are trying to fit a square peg into a round aspect-ratio hole. The advent of AI and ChatGPT has resulted in a wave of users imparting modern tech onto the art of the past, like using AI to “complete” Keith Haring’s famous Unfinished Painting.

“Right now, we don’t really have structures or frameworks for engaging with A.I.” researcher Tina Tallon told Smithsonian Magazine, “Or engaging with generative AI in a way that I think fully respects artists and the agency of artists and their agency over their own creative work, whether living or dead.”

And what does that mean for the archive, if all films of the past will be interspersed, just a little bit, with the future? AI ‘upscaling’ technology can now be used on old YouTube videos, and it’s only a matter of time before streaming services begin automatically upscaling classic films. No wonder Christopher Nolan told us to buy more DVD’s. With film studios willing to play it fast and loose with their own legacy libraries in favour of a quick buck, the actual long term preservation of classic media becomes more tenuous, especially without protections against AI restoration.

But the future is an invasive force. In 1987, when Ted Turner bought MGM, he announced plans to colourize over 100 classic black-and-white films that were in the acquisition, including Casablanca and It’s a Wonderful Life. In response, numerous actors and directors appeared in front of Congress to challenge Turner’s plans, arguing that black-and-white film is an artistic medium in itself worthy of respect, and to change it against the director’s wishes is “a transparent attempt to justify the mutilation of art for a few extra dollars.”

“The argument that one should not even ‘tamper’ with a work of art… seems to me to go hand in hand with that chilling argument that the public lacks the wisdom and sophistication to be allowed a choice in this matter,” argued Turner Entertainment president Roger Mayer. “You won’t read Chaucer in Middle English? Too bad, but you won’t have the chance to read him in a more palatable form because we've burned all the modern English versions.”

This is a perilous argument given that translation is an art form in itself, one which involves highly specific training to preserve meaning across text so that nothing gets lost in translation. Readers debate which English translation of Dostoyevsky is the most faithful, but in the future perhaps we’ll all be debating which 60fps AI upscale of Casablanca is the most authentic. That is, if those archives even still exist: consider what’s become of Ted Turner’s brainchild, Turner Classic Movies, gutted with layoffs and placing the entirety of Golden Age film preservation into peril along with it. We can modernize all we want—colourize old films, censor the harms of the past through the lens of the present—but that won’t keep the future from seeping in. In fact, the future is already here, and we are already there.

*

As a grad student I was responsible for teaching a weekly seminar to first-year undergrads. On the first day of class, I walked in and did the same thing every professor I’ve ever had has also done to me: I asked them to grab a pen and paper to make a sign for their names. They stared silently at me from behind their laptops, wide-eyed and confused. No one moved for their bags, despite my urging. Then I realized: none of them had paper with them. This was in 2019. Last week, a tweet about middle-school typing skills provoked the same sense of panic in me:

As a Gen-Z/Millenial cusp baby, I often joke with my more decidedly-Gen-Z friends about how “kids these days” just won’t understand what it was like growing up in the 90’s and early 00’s. I learned to type on computer programs that still used floppy disks to save. My family ordered takeout through the phone book and clothes through the Sears catalogue. We walked to the video store to rent VHS tapes, and we queued in line at the box office to buy our movie and concert tickets. I used to set my alarm clock by a telephone line you could call to give you the exact time. When the youngest of Gen-Z, born around 2012, turns of age, what message for the future will it carry from the past?

She’s still typing mrms…

Is it possible that we will reach a point where screens are so ubiquitous, their reflections so bright, that they no longer occupy a space in our lives, but vice versa? Ali Smith writes in Artful:

“At one level reflection means we see ourselves. At another, it’s another word for the thought process. We can choose to use it to look into the light of our own eyes, or we can be light sensitive, we can allow all things to move over and through us; we can hold them and release them, in thought. Broken things become pattern in reflection. The way a kaleidoscope works is to allow fragmentary or disconnected things to become their own harmony.”

*

But how to find harmony in the disconnect?

Consider the actions of the 20,000 textile workers in Nottingham who lost their jobs as a result of automation. In protest, the “beleaguered workers had begun breaking into factories to smash the machines” that had replaced them. Amidst escalating tensions, soldiers were deployed to the town in a tense stand-off between workers and state-backed factory owners. As one local newspaper described the scene: “God only knows what will be the end of it; nothing but ruin.” The workers who smashed the machines were part of a group that called themselves The Luddites. The year was 1811.

Of course, “luddite” today is a pejorative for someone opposed to new technology or ways of thinking. And how interesting, that the origin of a derogatory term for ‘anti-progressive’ stems in fact from a collective of workers fighting off their own redundancy.

*

With the trajectory we’re on, it seems inevitable that one day AI will be able to do for television what it can already do for still media, that is: fill in the rest of the frame for us, so nothing we love ever has to end.

I’ve been watching the Sopranos for the first time, just in time for its 25-year anniversary. I was 13 when the controversial finale first aired in 2007, its ambiguity so polarizing that it’s still discussed endlessly to this day. I’m halfway through the series, and I’m already dreading reaching the end.

Maybe one day I’ll be able to log into whatever AI generator replaces TikTok and type in: Sopranos if it never ended, and watch Tony Soprano on loop looking up forever, no cut to black, just a man staring into the void.

I’ve been aware of people using AI to mess around with classic artworks, but had no idea that studios/streamers were messing around with aspect ratios - that’s insane! would just love for everybody to accept a work of art as it is, rather than optimize it into oblivion

Loved this piece Raquel! For book club I recently read Ted Chiang's short story collection Exhalation. One of the stories, The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling, is about a world in which humans wear a camera at all times, creating a "lifelog" that they can refer back to. The piece discusses how this technology changes how people view themselves and their lives, how they communicate and how the concept of memory has changed and may continue to change. The story left me with the same sense of dread that reading the "mmrse" anecdote did.